Dr. Jan Niederau, ETH Zurich

December 2018

November 2021

https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000575831

Bundesamt für Landestopografie (swisstopo)

Bundesamt für Energie (BFE)

Prof. Martin O. Saar, Zurich

Dr. Jan Niederau, ETH Zurich

December 2018

November 2021

https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000575831

Bundesamt für Landestopografie (swisstopo)

Bundesamt für Energie (BFE)

Prof. Martin O. Saar, Zurich

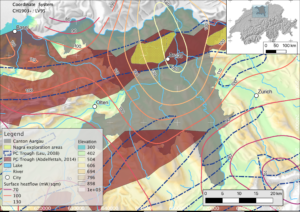

This pilot project aims at characterizing the geothermal heat-flux distribution in the Canton of Aargau to aid in the estimation of its geothermal potential. In Northern Switzerland, surface heat fluxes can reach up to 140 mW m-2, significantly higher than the Swiss average (Medici and Rybach, 1995). This may be caused by advective heat transport along Paleozoic faults in the crystalline basement. These are most likely normal faults bounding a major Permo-Carboniferous trough in the northern part of the Canton of Aargau (see Fig. 1). However, different explanations for the high surface heat fluxes exist, for instance, that two topographically driven flow regimes, southward from the Black Forest, and northward through the Mesozoic Molasse, meet in the project area and create a heat-flow anomaly as a consequence of upwelling. This formed surface-heat-flow anomaly would not be bound to fluids ascending along faults in the crystalline basement. Part of this project is to test these hypotheses, concerning different groundwater flow systems causing a heat-flow anomaly in the Canton Aargau (Figure 1) by using numerical modeling.

The project’s main objective is to produce model-based maps of the deep heat flow in the area as a reference for decision makers for potential future geothermal projects. These maps will comprise average heat-flow values at a depth of several kilometers, as well as their uncertainty. This is to be achieved by combining (geometrical) uncertainty of geological 3D models with (parametric) uncertainty of numerical heat-transport models in a Bayesian framework (de la Varga et al., 2016; Schneeberger et al., 2017; Wellmann and Caumon, 2018). Modelling and uncertainty evaluation will be integrated in an adaptive workflow which, in future, may be used for similar studies in other regions.

Figure 1: Our map of the project area in the Canton Aargau. Permo-Carboniferous troughs are outlined based on Leu (2008) and Abdelfettah (2014). The heat-flow contours are based on Medici and Rybach (1995).

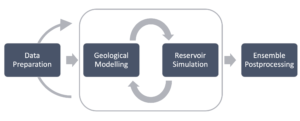

An integrative, adaptive, and reproducible workflow is at the core of this project, and comprises four major steps as depicted in Figure 2.

The initial step “Data preparation” comprises a multitude of tasks such as homogenization and standardization of data based on Strasky et al. (2016), who developed a lithostratigraphic lexicon of Switzerland, with the aim of harmonizing the existing lithostratigraphic nomenclature.

In the chosen method of handling legacy data, an iteratively built geological model does not necessarily have to fit single data points, but it is also used to test data. This approach, based on Corbel and Wellmann (2015), enables a modeler to distinguish between (model-)consistent data and (for the model) unusable data.

Steps Two and Three, namely “Geological Modelling” and “Reservoir Simulation”, are an iterative process, where a suite of different geological model hypotheses is evaluated by numerical simulation of the gravity response, as well as heat and mass transport in the geological model. The final result will likely be an ensemble of conditionally probable geological structures, whose response fit gravity measurements and measured temperatures in the study area.

Figure 2: Simplified depiction of the project workflow, based on four major steps.

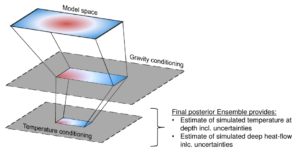

The sequential conditioning of an ensemble of geological models is depicted in Figure 3. A pre-existing model space of possible geological structures, called the prior ensemble, will be sequentially conditioned based on its modeled gravity response and measured borehole temperatures in the study area.

The resulting posterior ensemble will then comprise geological models, whose gravity simulation as well as heat transport simulation, fit the respective data.

Figure 3: Depicted conditioning workflow of the prior ensemble.

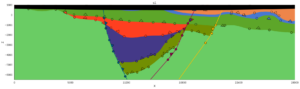

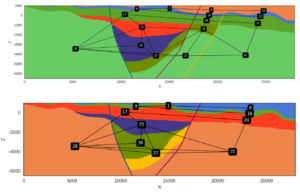

For modeling the spatial geometry of geological structures and lithologies, we test an implicit potential-field approach (Lajaunie et al., 1997; Wellmann and Caumon, 2018; de la Varga et al., 2019). In Figure 4, the two input data types for the model are shown: interface points (colored circles) and orientation points (colored arrow heads), based on seismic interpretations by Naef and Madritsch (2014). The resulting simplified, discretized 2D model of a Permo-Carboniferous trough is shown as colors. In addition to interpreted seismic section, existing geological models, such as GeoMol (GeoMol Team, 2015), or borehole lithology will be considered and merged with the model hypotheses in the presented modeling workflow.

For modeling the spatial geometry of geological structures and lithologies, we test an implicit potential-field approach (Lajaunie et al., 1997; Wellmann and Caumon, 2018; de la Varga et al., 2019). In Figure 4, the two input data types for the model are shown: interface points (colored circles) and orientation points (colored arrow heads), based on seismic interpretations by Naef and Madritsch (2014). The resulting simplified, discretized 2D model of a Permo-Carboniferous trough is shown as colors. In addition to interpreted seismic section, existing geological models, such as GeoMol (GeoMol Team, 2015), or borehole lithology will be considered and merged with the model hypotheses in the presented modeling workflow.

Figure 4: Simplified 2D geological model based on the interpretation of seismic line 11-NS-06 by Naef and Madritsch (2014).

For analysing the influence of different geological concepts in an ensemble framework, we assess the model topology. Topological graphs, as shown in Figure 5, easily depict, which geological units have a direct connection in space. Thus, depending on the geological concept (e.g. do we have multiple normal faults bounding the graben), the resulting topological graph will be different. Consequently, unique topological graphs can be considered as a conceptual geological model.

Figure 5: Topological graphs of two different conceptual geological models, differing in the number of normal faults (yellow fault on the right).

Deviations within an ensemble of geological models, caused by spatially uncertain input data, are visualized using information entropy. Information entropy is a measure useful for assessing (un)certainty. Higher entropy values correlate to a higher spatial uncertainty, but also indicate areas in a model, where acquiring new data may have the highest information gain.

While simulation of the gravity response of a geological model is implemented within GemPy, heat transport simulations will be performed in a different software.

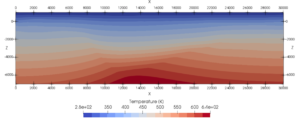

Geological models constraint by gravity (see Figure 3), are transferred to a framework for simulating fluid mass and heat transfer (MOOSE framework; Gaston et al., 2009). It provides a porous flow module comprising all necessary governing equations for simulating fluid mass and heat transport in a geothermal reservoir system (e.g. Figure 6).

Calibrated simulation results will be merged in an ensemble comprising model realizations conditioned by gravity and temperature data. This ensemble is then used for generating the aforementioned heat-flow maps with associated uncertainty.

Figure 6: Preliminary, purely conductive temperature field simulation of the modeled geological cross-section in Figure 3. The shape of the graben system can be inferred, due to the different thermal conductivities of the lithological units.

Abdelfettah, Y., Schill, E., and Kuhn, P.: Characterization of geothermally relevant structures at the top of crystalline basement in Switzerland by filters and gravity forward modelling. Geophysical Journal International, 199(1), (2014), 226-241.

Corbel, S., and Wellmann, J. F.: Framework for multiple hypothesis testing improves the use of legacy data in structural geological modeling. GeoResJ, 6, (2015), 202-212.

Gaston, D., Newman, C., Hansen, G., and Lebrun-Grandie, D.: MOOSE: A parallel computational framework for coupled systems of nonlinear equations. Nuclear Engineering and Design, 239(10), (2009), 1768-1778.

GeoMol Team (2015): GeoMol – Assessing subsurface potentials of the Alpine Foreland Basins for sustainable planning and use of natural resources – Project Report, 188 pp. (Augsburg, LfU).

Lajaunie, C., Courrioux, G., and Manuel, L.: Foliation fields and 3D cartography in geology: principles of a method based on potential interpolation. Mathematical Geology, 29(4), (1997), 571-584.

Leu, W.: Permokarbon-Kartenskizze (Rohstoffe). Kompilation eines GIS-Datensatzes auf der Basis von bestehenden Unterlagen (Bereich Schweizer Mittelland). Nagra Arbeitsber. NAB 08-49, (2008).

Medici, F., and Rybach, L.: Geothermal map of Switzerland 1995:(heat flow density) (No. 30). Commission Suisse de géophysique, (1995).

Naef, H., and Madritsch, H.: Tektonische Karte des Nordschweizer Permokarbontrogs: Aktualisierung basierend auf 2D-Seismik und Schweredaten. Nagra Arbeitsbericht NAB 14-017, (2014).

Schneeberger, R., de La Varga, M., Egli, D., Berger, A., Kober, F., Wellmann, F., and Herwegh, M.: Methods and uncertainty estimations of 3-D structural modelling in crystalline rocks: a case study. Solid Earth, 8(5), 987-1002, (2017).

Schärli, U. and Kohl, T.: Archivierung und Kompilation geothermischer Daten der Schweiz und angrenzender Gebiete. ISSN 0253-1186, Swiss Geophysical Commission (Beiträge zur Geologie der Schweiz: Geophysik, Nr. 36), (2002).

Strasky, S., Morard, A., and Möri, A.: Harmonising the lithostratigraphic nomenclature: towards a uniform geological dataset of Switzerland, Swiss J Geosci 109(2), (2016), 123-136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00015-016-0221-8

de la Varga, M., Wellmann, F.: Structural geologic modeling as an inference problem: A Bayesian perspective. Interpretation, 4 (3), (2016), SM1–SM16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1190/INT-2015-0188.1

de la Varga, M., Schaaf, A., and Wellmann, F.: GemPy 1.0: Open-source stochastic geological modeling and inversion. Geoscientific Model Development, 12(1), (2019), 1. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-1-2019

Wellmann, F., and Caumon, G.: Chapter One – 3-D Structural geological models: Concepts, methods, and uncertainties. Advances in Geophysics, 59, (2018), 1-121.